My pick, fortunately, is still with us, but would not be overly enthusiastic for an interview.

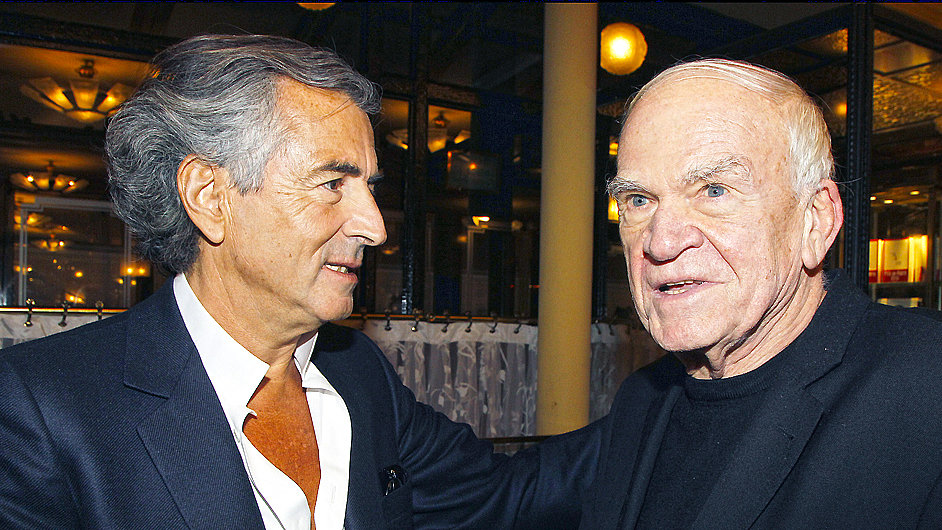

A Czech I’m interested in interviewing is author Milan Kundera. According to Wikipedia, Kundera is Czech Republic’s most recognized living writer. He is Czech by ethnicity, but since moving to France in exile in 1975, he considers himself French. As a lover of literature and a creative writing minor back in the United States, I was immediately drawn to Czech writers. Some of his works were banned during the Communist regime until the Velvet Revolution of 1989. He has been nominated multiple times for the Nobel Prize in Literature.

It seems that most of Kundera’s novels are satirical and political in nature. He has been quoted asserting that he does not want be labeled as a “novelist” and more so a political writer – though I think that the public would have a different opinion. His writing style can be classified as stream of consciousness; he cared little about the physical world of his characters, and more their state of mind. His early novels explored the duality of totalitarianism mostly focusing on the dichotomy of comedy and tragedy. He cares much more about being ironic than having a message, which seems to divert from other artists of the Velvet Revolution.

Despite having many critics, his work has received many accolades. In 1985, Kundera received the Jerusalem Prize, which is a biannual literary award given to writers whose works deal with themes of human freedom. In 2007, he was awarded the Czech State Literature Prize. In 2010, Kundera was made an honorary citizen of his hometown, Brno. Kundera is still alive at the prime age of 85, though lives virtually incognito in France and rarely interacts with the media.

Three questions I’d love to ask Kundera:

1) What were the reasons that drove you away from media communication and into a non-descript life?

2) Do you think that your perception as a Czech writer as opposed to a French writer generalizes you more as a revolutionary writer than an overall “artist”?

3)What do you think of future generations reading your work and attempting to draw out deep political messages from pieces you believe are simply ironic?

Here's what some of my classmates had to say:

Robyn Cho: Adriena Simotová was a famous Czech artist who was a painter, a graphic artist, and a sculptor. Her most popular medium was working with white handmade paper and fabric, but she is also known for paintings and graphic art with vibrant colors. Throughout all her works, she illustrates her immense interest in human relationships and going beyond the physical exteriors of the human body in her work.

Much of her work reflects the different emotions she felt throughout her life and her experiences. During the 60s, she was a part of UB 12, a group that influenced a great amount of her work. In the 70s, she used a lot of vibrant colors in her graphics and collages. One of the turning points in her life was when her husband died, causing her to leave behind the traditional painting medium and create new techniques with paper, which contributed to the revitalization of the Czech art scene after the Velvet Revolution. Her emotions of pain are shown through her artwork in this period through her choice of using paper instead of paint and the fading colors in her pieces. Additionally, her work represents her intrigue in human relationships, taking her pieces beyond the personal and allowing the viewer to relate to her messages.

Much of her latter work is very simple with few colors, but the ambiguity of the shapes and vague figures throughout her pieces draws in the audience to question the meaning behind her works. Additionally, Adriena Simotová’s techniques with paper combined with few colors creates a feeling of entrapment of the figures, which could represent her distraught after her husband’s death. Her use of different mediums throughout her life represents how she utilized her emotions and interests in her works. Since her art is filled with emotions, it evokes similar feelings among her audience.

Questions:

1. How do you think the use of paper illustrated your emotions of sadness after your husband’s death?

2. Do you think your art’s purpose is to evoke similar emotions from the audience? What is your message?

3. If you could choose another medium to work with, what would it be?

Jordana Norry: Growing up, my least favorite class was always English. I just never understood why my teachers found such pleasure in digging for what was wrong in my essays, rather than appreciating my hard work. Furthermore, I never understood a piece of literature required so much deep analysis. Couldn’t we just read the book and simply enjoy it? As you can tell, definitely didn’t enjoy English class. Therefore, if I were to meet one famous Czech it would probably be Franz Kafka. Are we actually interpreting his novels in the manner that he intended? Did he expect for his novels to be so deeply analyzed?

More so than any other famous Czech author, Kafka works is still so highly regarded and influential in the English-speaking world. I am curious to hear how he feels about the ways in which literature is analyzed and taught today. Perhaps he may justify my hatred towards the high school English curriculum.

Questions –

1. How closely connected were you to your Judaism? How did this influence your writing?

2. How do you feel about your works being published after your lifetime? Is this what you expected/intended?

3. How has the world of English and literature transformed over time? Do you appreciate the way in which novels are analyzed today? Especially your own?

Darbus Sinjem: The person I have chosen to interview out of any Czech citizen of the past would the photographer Josef Sudek. I would want to interview him because I am very passionate about my photography and I really admire his work, especially the photos he has taken of Prague. The three questions that I would ask him during interview are as followed:

Questions:

1. Do you think you would have ever taken up photography if it weren’t for your injury you sustained in the war?

2. Where would you say you get your inspiration for the artwork you do?

3. Where do you do say is the most beautiful place you have photographed in your life?

Carly Berizzi: If I could sit down with one person from Czech history and ask them a few questions it would be Alphonse Mucha, a famous Czech artist who died in 1939. Mucha is interesting to me because of his revolutionary work. The beauty and detail of Mucha’s work is incredible and the attention to detail is fascinating. I would love to talk to him about my personal favorite, “The Slav Epic”, which is a series of 20 enormous paintings showing the history of the Czech and Slavic people. Each painting took him about a year to make, primarily because of the massive size of the pieces. Being a studio art minor, I have taken art history classes which have touched upon his work which is why I feel as if he would be a perfect person to interview.

Questions:

1. Despite a lack of accessibility to large canvases, you created grand paintings. Why not scale down some of the work so that the canvases you wanted were more readily available?

2. Why when all of your peers were pushing boundaries and doing very foreign work did you decide to keep with the idea of perfection and beauty?

Caitlin Dwyer: I had the opportunity to interview any deceased Czech person, I would choose Jan Palach. I would choose Jan Palach because of his role in Czech history. He committed suicide by self-immolation as an act of political protest against the occupation of Czechoslovakia. Palach was a symbol of the demoralization of Czechs due to the Soviet occupation. He was commemorated in many ways: squares and streets were named after him and memorials were created in his honor. If I had the chance to interview him, this is what I would ask him:

1. Do you believe that what you did, the statement you made, was successful? Do you believe that it had the impact that you were intending it to have?

2. Were you hoping that others would follow in your footsteps and immolate themselves for the cause just as you did and as you said in your notes that were uncovered after your death? Or did you intend for your notes to scare the government in such a way that it would inspire change?

3. If you could go back in time to 1969, what would you directly say to the Soviet government occupying Czechoslovakia?

Jenna Jiampietro: Jane Ciglerova is a highly respected Czech journalist and women’s rights activist. After recognizing her passion for writing and immense drive to succeed at a young age, Ciglerova attended Czech journalism school and was the first student to receive a scholarship from the British Embassy to study abroad in London. In London, she received her M.A. in international journalism, which kick started her career.

One of her first jobs was as a U.K. correspondent for Lidove Noviny, where she was able to learn how to write in English. She quickly became involved in an undercover story, where Ciglerova along with another journalist exposed a number of schools handing out visas illegally. With her name and face in the public eye, Ciglerova was quickly offered internships at some of the most prestigious publications including the Guardian and Telegraph. Since, she has written and worked for a wide variety of publications including The Observer. Among other titles she has held the position of editor in chief at Elle Magazine, a title she accepted in order to gain access to a broad number of women reader in an attempt to promote women’s issues. She more recently has contributed to The Daily Mlada Fronted Dnes and launched her own women’s weekly called Ona. Ciglerova currently produces a TV show called Tah Damouh, a show where women discuss pertinent issues.

This piece was also edited by Sarah Mae Alcorn.